Discuss E-List

Essential Resources Guide

FREE Teaching Resources

Membership Benefits

Partner Discounts

Summit 2006

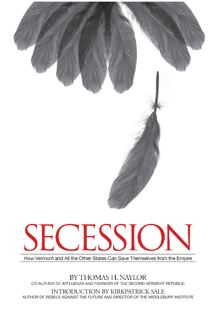

BOOK REVIEW: Secession

It is always appropriate, in my mind at least, to write one’s last media column of the year about the most interesting media text one has discovered over the past year.

For me, that media text would have to be Secession.

Charlotte, Vermont’s Thomas Naylor is a former international businessman, professor emeritus of Duke University (in economics), and the chair of the Second Vermont Republic, a think tank devoted to advancing the radical but very American idea that the state of Vermont should nonviolently secede from the United States and govern itself as an independent republic once again, as it did from 1777 to 1791.

He’s outlined the case for secession, Vermont-style, in a book with the same title (see above) and, to this reader, it is worth a close read.

Full disclosure.

As the editor and publisher of Vermont Commons: Voices of Independence news journal, I believe (as Naylor does) that the idea of secession merits serious exploration. And, while he and I differ in terms of our tone and tenor, style and strategy, I submit that the idea of secession is an idea whose time has come.

Before you scoff, consider a few facts, to be submitted (as Jefferson suggested) to a candid world.

Secession is as American as apple pie. The United States was born out of secession, as the thirteen English colonies left Great Britain’s imperial orbit and crafted a new republic for themselves (Vermont, of course, beat them to the punch – establishing itself as an independent republic fully seven years before the 1783 Treaty of Paris was signed, creating the new United States.) The 1776 Declaration of Independence’s central theme is, of course, secession – and the very first verb Jefferson and the first Continental Congress use is “dissolve.”

Contrary to what we learned in school, the first region of the U.S. republic to seriously consider secession was not the South (mention the word “secession” to most Americans, and, assuming they can spell the word correctly, their first impulse is to conjure images of plantations, slaves, and mint juleps). But it was 18th century New Englanders (Vermonters included, as Vermont joined the United States in 1791) who seriously considered secession on no fewer than six occasions between the 1787 signing of the U.S. Constitution and the so-called “Civil War” of 1861-1865 (really a “War to Prevent Southern Secession,” but Lincoln’s radical re-invention of the U.S. Constitution won the day, with the help of Union bayonets and the lives of hundreds of thousands).

Why is secession worth another look in this new century?

In his short and accessible book, Naylor suggests that the United States is no longer a republic but an Empire that is essentially ungovernable and unsustainable. In what he calls an “endgame for America” scenario, he sees the 1990 collapse of the Soviet Union as an omen for the United States, and points to the scourge of “bigness” as the chief problem facing Americans today – big government, big business, and big militarism – and explains that the problem with the United States is ultimately one of size and scale, beyond the range of one person, party, platform or program to fix (“hope and change” rhetoric notwithstanding.)

But the strongest part of the book, in my mind, is Naylor’s celebration of Vermont’s unique virtues as one of the tiniest and most decentralized states in the U.S. Our Vermont communities, Naylor suggests, offer an ailing United States a new way forward, a new metaphor: of small schools, small businesses, small towns, and small communities. It is this decentralized and small scale model that provides the blueprints. What if Burlington became the music capital of the northeast, with its network of concert halls, studios and recording talent? Could Vermont cheesemakers set high artisanal standards for the continent (they already do, in my book)? What of our syrup, farm and forest industries? What if, Naylor suggests, Vermont becomes the Switzerland of North America?

At a time when the United States seems to be teetering on the edge of the abyss, Vermont independence is an attractive notion. The book’s biggest weakness, however, is its refusal to specifically grapple with the kinds of economic changes that will move Vermont from here to there. 21st century Peak Oil realities, for example, demand that we in Vermont re-invent the ways we power our homes and businesses, feed our communities, and transport ourselves from place to place. Naylor shies away from confronting specific “nuts and bolts” questions like these – which is too bad, because his business and scholarly experience would no doubt prove invaluable.

But Naylor’s Secession, a celebration of Vermont’s past, present and potential vis-à-vis a crumbling United States, is the single best book-length starting place for considering a conversation about what Vermont could be in the 21st century and beyond.

An independent republic? An “Untied States?” A new metaphor for a new millennium?

Time will tell.

![View your cart items []](/sites/default/modules/ecommerce/cart/images/cart_empty.png)